A Closer Look at Transit

Disclaimer: I am an employee of Cognitect and I worked on the transit-js implementation. The opinions found herein are my own and do not necessarily reflect the recommendations or views of Cognitect.

By now you may have heard of something called Transit, a new format for conveying values between heterogenous systems. Transit seemed to generate a lot of interest, but given many of the comments on the announcement post and elsewhere like Hacker News, it seems that people may be unclear about the value proposition.

Admittedly this state of affairs is not entirely the fault of the audience. I’ve had the pleasure of using software designed under the guidance of Rich Hickey for seven years now. Often his design decisions cover nuanced territory with far more dimensions than can be communicated in a short introduction. I’ll try here to illuminate some properties of Transit that I think might easily be overlooked. We’ll make some of these points concrete via an example in Node.js (Ruby, Python, Java, and Clojure work just as well). We’ll communicate with client-side JavaScript, but you can use whatever compile-to-JavaScript language you prefer.

But before we do any of that, let’s first address something that appeared with surprising frequency following the announcement - “Why not use existing data format X instead?”. This kept getting asked even though the third sentence of the announcement post read:

JSON currently dominates similar use cases, but it has a limited set of types, no extensibility, and is verbose. Actual applications of JSON are rife with ad hoc and context-dependent workarounds for these limitations, yielding coupled and fragile programs.

Yet people continued to enumerate existing formats which do not actually compete in the same design space as JSON. If you only use a binary data format to convey values in your heterogenous system, you are unlikely to be the target consumer of Transit. However, if some components of your system marshal JSON and you would prefer something comparable in performance to JSON when communicating with those components, then Transit is well worth thinking long and hard about.

As to to why transit-js doesn’t yet use the binary msgpack encoding, benchmarking has shown that existing binary formats don’t yet compete with JSON in many JavaScript environments (see footnote (1) at the end of the post). Currently transit-js compares quite favorably to plain old JSON (see footnote (2)).

Let’s consider a typical API result, for example the JSON response from Twitter’s search api:

{

"statuses": [

{

"coordinates": null,

"favorited": false,

"truncated": false,

"created_at": "Mon Sep 24 03:35:21 +0000 2012", // SAD PANDA

"id_str": "250075927172759552",

...

"in_reply_to_user_id": null,

"place": null,

"user": {

"profile_sidebar_fill_color": "DDEEF6", // BOO

"profile_sidebar_border_color": "C0DEED", // HOO

....

"profile_image_url": "http://a0.twimg.com/...", // :( :( :(

"created_at": "Mon Apr 26 06:01:55 +0000 2010", // ARGH!

...

"profile_link_color": "0084B4", // RAGE!

...

},

...

},

...

]

}

Obviously we can represent strings and some numbers just fine with JSON - but

fields like created_at, profile_image_url, profile_sidebar_fill_color,

profile_link_color, etc. have lost their meaning. It’s likely that this JSON

response was generated with URI and DateTime and Color instances in hand,

but on the wire they simply become strings. The receiver now must know which

parts of this response represents which values.

Contrast this to a transit-js value before encoding where t is the transit

library, URI is the constructor from the

URIjs library, moment is

moment.js, and color is

onecolor:

t.map([

"statuses", [

t.map([

"coordinates", null,

"favorited", false,

"truncated", false,

"created_at", moment("Mon Sep 24 03:35:21 +0000 2012"), // YAY!

"id_str", "250075927172759552",

...

"in_reply_to_user_id", null,

"place", null,

"user", t.map([

"profile_sidebar_fill_color", color("DDEEF6"), // YIPPEE!

"profile_sidebar_border_color", color("C0DEED"), // WOOT!

...

"profile_image_url", URI("http://a0.twimg.com/..."), // HURRAH!

"created_at", moment("Mon Apr 26 06:01:55 +0000 2010"), // WIN!

...

"profile_link_color", color("0084B4"), // HALLELUJAH!

]),

...

]),

...

]

])

When this value is written out, Transit does not discard the important semantic information needed to interpret this data upon arrival at the client. If we’re using JavaScript on the front and back end, it’s simple to share handlers so that we get the same types in both places - “isomorphic” JavaScript people.

Or, if you’re writing Java, it’s nice to know your Joda Time instances become Moment instances on the front end and so forth.

Now let’s contrast using JSON versus using transit-js on the front end. Notice below that in the case of transit-js the types are always the ones you expect: no need to remember which date format or what color library was agreed upon. Just start programming!

(function(g) {

var j = g.jQuery,

h = g.transitHandlers,

rdr = g.transit.reader("json", {handlers: h.readHandlers});

// Reading transit, values are already the types your team expects

// just start programming

function parseTransitStatus(status) {

var user = status.get("user");

return {

weekLater: status.get("created_at").add("days", 7),

color: user.get("profile_sidebar_fill_color").cmyk(),

url: user.get("profile_image_url").path()

};

};

j.ajax({

type: "GET",

url: "transit",

complete: function(res) {

var data = rdr.read(res.responseText),

xs = data.get("statuses").map(parseTransitStatus);

console.log(xs);

}

});

// Reading JSON, you always need to remember exactly what to hydrate

// to which types your team has agreed upon

function parseJSONStatus(status) {

var user = status["user"];

return {

weekLater: new Date(status["created_at"]).add("days", 7), // OOPS!!!

color: user["profile_sidebar_fill_color"], // BLAST!

url: URI(user["profile_image_url"]).path()

};

}

j.get("json", function(data) {

var xs = data["statuses"].map(parseJSONStatus);

console.log(xs);

});

})(this);

With fast ES6-like maps and sets and user extensibility baked in, you can transport values that best describe your application without chaining yourself to the representational boundaries imposed by JSON.

But at what cost?

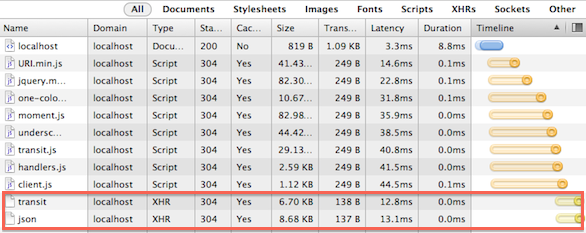

The transit-js version of the original Twitter payload is smaller and does not take measurably longer to transmit to the client.

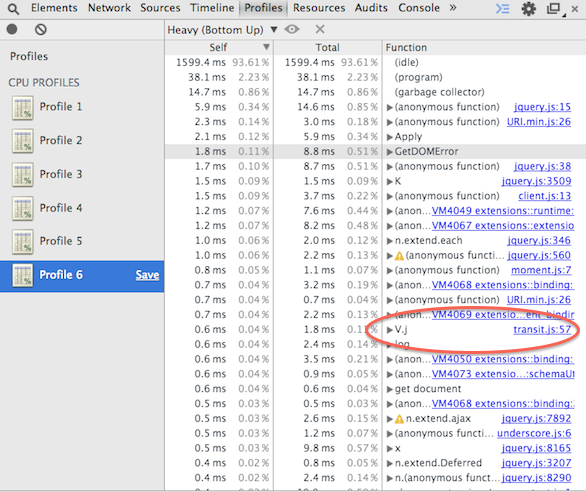

Here’s a Chrome DevTools JavaScript profile to determine where our program is spending its time. Note how far down the profile transit-js appears:

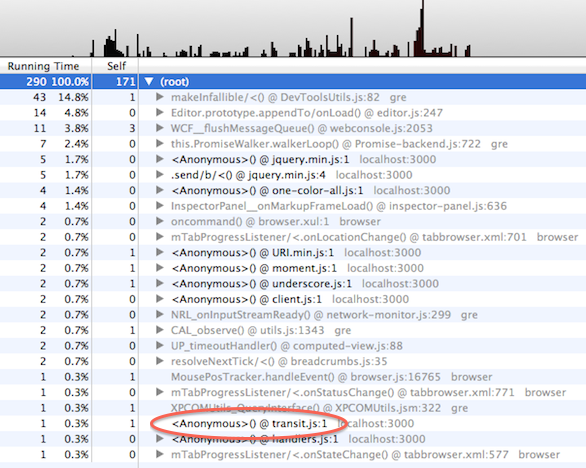

What about Firefox?

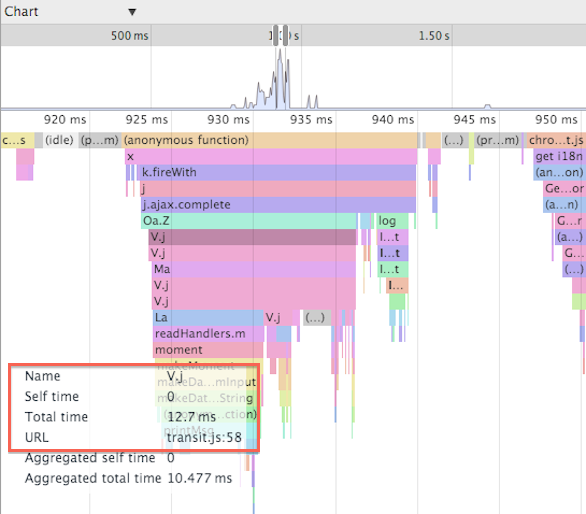

If we dig in a bit more and check out the flame graph, we’ll see something like this:

V.j is the call into transit-js. Note the self time. This means transit-js is

unlikely to be the bottleneck; rather, the bottleneck will be whatever

particular type you wish to hydrate with.

You can profile under Opera, Safari, and Internet Explorer: the results will be much the same.

You can find the entire example shown here on GitHub.

If you’d like to play around with transit-js without installing Node.js, I recommend taking a look at the tour.

(1) msgpack vs. JSON benchmarks.

(2) transit-js vs. JSON.